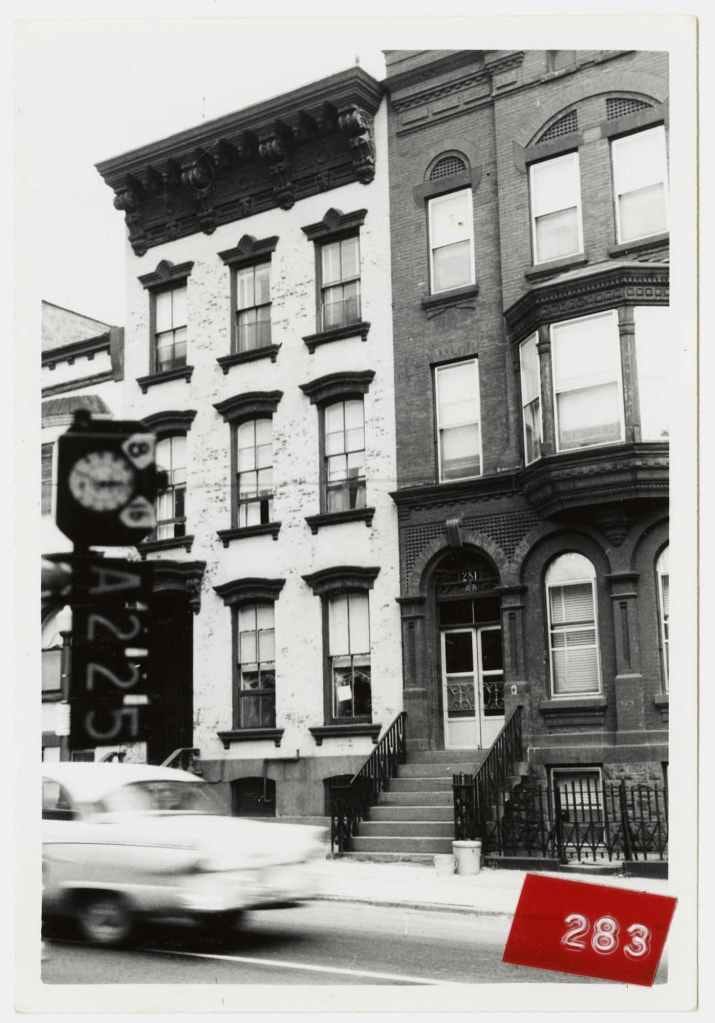

The neighborhood that was demolished to make way for the Empire State Plaza

Reflecting on vibrant, diverse communities and electing politicians that work for all of us (not just the wealthy)

This morning I went to a showing of The Neighborhood That Disappeared1, a documentary about the 98 acres of Albany neighborhood that Governor Rockefeller demolished to make way for the construction of the Empire State Plaza in the 1960s. I’ve seen it before and read a lot about this so-called urban renewal project. I usually focus in on the policy side — the claim of eminent domain, the destruction of the built environment, the gargantuan plaza that is totally out of human scale. Today, the stories struck me differently.

The neighborhood that was destroyed was a neighborhood of immigrants, most commonly known as part Albany’s South End. There were Italians, Irish, French, Chinese, Jewish and Black families who ran businesses, watched each other’s kids and made downtown Albany a thriving, vibrant place to live. Nostalgia can be a dangerous thing, but nevertheless I was moved by the descriptions of the neighborhood. In contrast to what Governor Rockefeller claimed at the time, it was not “one of the worst slums” in America, neither was it plagued by a high rate of infant mortality. White flight to the suburbs was underway, yes, and we’re all too familiar with the wrath that bank redlining and housing discrimination wrought on downtown neighborhoods.

And yet, the interviewees from the film describe the South End as a place where everyone gathered on their front stoops after dinner and caught up, told jokes, played music and watched out for the little ones. It was a place where families shopped for groceries like they do in Europe, going from one mom-and-pop grocer to another all down the block. The Catholics gathered at St. Anthony’s (now home to Grand Street Arts) and held religious and cultural festivals. It was a neighborhood filled with stores, theaters, pharmacies, doctors and dentists offices and people.

It’s true that many families were poor.2 They shared what they had. They shared responsibility for one another. They were their neighbor’s keeper. We won’t glamorize poverty or the ways in which, even in this neighborhood, privileges accrued differently across racial and ethnic lines. But we can learn from what worked. We can model how people at that time, in that neighborhood, lived in community rather than within the confines of the nuclear family. We can admire the ethos of small business entrepreneurship and try to understand the social, political and economic environments that made it possible. We can look at well-intentioned zoning requirements that also created the rise of use-segregated neighborhoods, increased commute times and fueled segregation.

Governor Rockefeller used the power of eminent domain to seize these 98 acres, some 40 city blocks, to tear it down completely and displace more than 7,000 people. And because it was a community of mostly immigrant, Black or brown families, they didn’t have enough power to defeat the whims of a billionaire politician who saw nothing but a blank slate where he could improve the view from his office window with acres of white marble development.

A timely reminder that we need politicians that work for all of us, not just the wealthy.

Two other reminders.

Immigrants and newcomers make our community so much better. I’m reminded every day how much richer our community is because of the immigrant and refugee families living here. Here in Albany, I’ve been able to see the slow transformation of neighborhood blocks from underdeveloped and blighted to bustling, family-filled hubs of activity. One person I spoke with says his own neighborhood is coming back from decades of disinvestment and neglect because a new immigrant population has moved in and planted roots! About half of recent Habitat homebuyers came to Albany as immigrants or refugees and they are helping to stabilize and revitalize our community, home by home.

Mixed use, mixed income neighborhoods ought to be the goal. Where homes and shops and offices all line the same block. Where you do your shopping nearby instead of driving out to the commercial strip of chain retailers. I’m paraphrasing here, but one interviewee said you could live your whole life in that neighborhood with everything you needed. Imagine?!

It’s election season. You know what to do.

💌 1,350 letters to voters

💬 8 hours of text banking

☎️ 1 hour of phone banking

🌎 14 volunteers on my Build the Climate Vote team

🤳🏻 84 selfie postcards sent on behalf of WFP

ONE BALLOT CAST FOR HARRIS/WALZ and progressives down the line mostly on the Working Families Party Row D, plus YES on NY’s Prop 1💙 (These votes, of course, represent my personal views and values.)

Elsewhere

I am very excited for this upcoming event: Building Connections with Habitat Capital District and Mexico on Tuesday, November 12! Two colleagues I met during my trip will be in Albany on November 12, and we’re having an meet and greet with them! We’ll have presentations about the work Habitat is doing locally and throughout Latin America, including in Mexico.

We’ll have snacks and I’ve got it into my head that we might also have U.S. - Mexico friendship bracelets, so come through to see whether I make that last part a reality. We’re holding at the Ritmo Room, right across the street from Habitat’s office. For 20 minutes I thought we might combine the event with a short cumbia dance lesson. Alas, we aren’t. But maybe we should? If you’re coming, RSVP so we have enough snacks.

We have a lot of fun events coming up at Habitat — if you’ve ever wanted to connect with us outside the build site, check them out.

I can’t find the film online anywhere, but it looks like it’s available at a lot of area libraries if you’re local.

Here’s a really good piece from the All Over Albany archives about who lived in the neighborhood before it was torn down.

is there a streaming platform to watch this documentary? Would love to learn more about the origins of this